After developing a runtime packer in the last post, I tinkered with anti dumping techniques using PE Header manipulation. In this post I will talk about different approaches and take a look at the commonly used dumper ExtremeDumper.

*ConfuserEx AntiDump is not included in this article as it would be enough for an entire article

What is a memory dump?

A memory dump consists of the recorded state of the working memory of a computer program at a specific time. In our case this would be the state of the memory once an assembly is fully loaded.

A memory dump is typically used to extract dynamically loaded assemblies or information that is decrypted at runtime. This article will focus on dumping tools that dump an entire .NET assembly at runtime.

Why do people use AntiDump

Trying to prevent people from dumping your process memory can have many reasons. The most obvious reason would be runtime decryption for example the method body encryption used by ConfuserEx which will only decrypt the CIL method bodies on runtime. Meaning the easiest way to restore the CIL bodies is by dumping the app with the decrypted method bodies from memory.

Another obvious target for dumping are runtime packers that decrypt and invoke their payload on runtime. Instead of reverse engineering often heavily obfuscated code, you can simply dump the payload from memory.

Preventing a memory dump

Process names

In order to prevent a memory dump we can do a few things. The simplest solution you have probably seen many times, is checking for process names. If a known dumper process is found the app will trigger some action. However, this technique is quite trivial to bypass as one can simply rename their dumper. Not to mention a list of bad process names is an obvious flag for any reverse engineer. Another downside is the need to constantly monitor running processes.

Erasing PE Header data

Another commonly used anti dumping solution I have seen many times is erasing certain fields in the PE Header. Unlike native apps we cannot just erase the entire PE Header since it is used by the .NET CLR after initialization. Lets look into one of the most common classes used for erasing PE Header information.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

public static void AntiDump() {

var process = System.Diagnostics.Process.GetCurrentProcess();

var base_address = process.MainModule.BaseAddress;

var dwpeheader = System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal.ReadInt32((IntPtr)(base_address.ToInt32() + 0x3C));

var wnumberofsections = System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal.ReadInt16((IntPtr)(base_address.ToInt32() + dwpeheader + 0x6));

EraseSection(base_address, 30);

...

Code by Mecanik, from here

First of all, we get the current process and the BaseAddress of its MainModule. The BaseAddress is the beginning of the current module’s PE Header. We continue by reading the value of e_lfanew, a field located in the DOS Header which contains the offset to the beginning of the File Header. The value is stored in the local variable dwpeheader. Next, we read NumberOfSections from the File Header. To obtain its address the value of dwpeheader and an offset of 0x6 is added to the BaseAddress.

Next off, EraseSection is called with the BaseAddress and 30 supplied as parameters. It overwrites the specified amount of bytes at the given address with zero bytes using the functions VirtualProtect and ZeroMemory exported by kernel32.dll.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

private static extern IntPtr ZeroMemory(IntPtr addr, IntPtr size);

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

private static extern IntPtr VirtualProtect(IntPtr lpAddress, IntPtr dwSize, IntPtr flNewProtect, ref IntPtr lpflOldProtect);

private static void EraseSection(IntPtr address, int size) {

IntPtr sz = (IntPtr) size;

IntPtr dwOld = default(IntPtr);

VirtualProtect(address, sz, (IntPtr) 0x40, ref dwOld);

ZeroMemory(address, sz);

IntPtr temp = default(IntPtr);

VirtualProtect(address, sz, dwOld, ref temp);

}

Let’s take a closer look at EraseSection. Initially VirtualProtect is called to set the protection for the desired memory region to PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE(0x40). Which enables read, write, and execution permissions for that region. Next, ZeroMemory is called on the before unprotected region, which will overwrite the specified region size with zero bytes. Finally, the protection of the region is restored to the previous protection by calling VirtualProtect again but with the old protection as the flNewProtect argument.

1

2

3

for (int i = 0; i < peheaderdwords.Length; i++) {

EraseSection((IntPtr)(base_address.ToInt32() + dwpeheader + peheaderwords[i]), 4);

}

The code continues with erasing some specific fields in the File Header, Optional Header, and the Section Table using multiple arrays of hardcoded offsets. This is done using multiple loops which iterate trough the arrays containing the offsets. For every offset it calls EraseSection using the following address chain: base_address + dwpeheader + the array value at index i.

I will not go over that part in too much detail, however I wrote a simple tool to map the offsets used in the code to their corresponding fields in the PE Header. The tool and a list of all the mapped fields can be found here, code is commented so you can follow the process.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

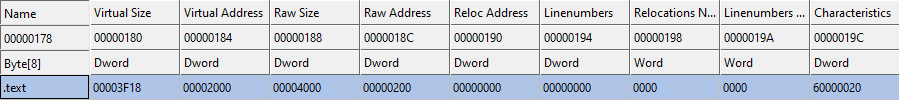

0x20 offset to Section_Linenumbers_Number in the Section Table => location: 0000019A

0x8 offset to Unknown in the Section Table => location: 00000182

0xC offset to Unknown in the Section Table => location: 00000186

0x10 offset to Unknown in the Section Table => location: 0000018A

0x14 offset to Unknown in the Section Table => location: 0000018E

0x18 offset to Unknown in the Section Table => location: 00000192

0x1C offset to Unknown in the Section Table => location: 00000196

0x24 offset to Unknown in the Section Table => location: 0000019E

If you check the full list you will notice a few fields mapped to Unknown, these are offsets that point to somewhere inside the Section Table however they seem to be incorrect as they don’t point to a specific field but only at data in between 2 fields. Take a close look at the locations shown in the above segement of the mappers output and compare them to the actual field offsets taken from CFF explorer.

You will see that the locations resolved by the mapper dont match with any of the field offsets that CFF Explorer shows. Instead they seem to be off by two, for example the first offset in the sectiontablewords array 0x8 results in the location 00000182 which is plus two off from Virtual Size and minus two off from Virtual Address. This might be intentional but I cannot make any sense of it.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

int x = 0;

int y = 0;

while (x <= wnumberofsections) {

if (y == 0) {

EraseSection((IntPtr)((base_address.ToInt32() + dwpeheader + 0xFA + (0x28 * x)) + 0x20), 2);

}

EraseSection((IntPtr)((base_address.ToInt32() + dwpeheader + 0xFA + (0x28 * x)) + sectiontabledwords[y]), 4);

y++;

if (y == sectiontabledwords.Length) {

x++;

y = 0;

}

}

This part contains the offsets that I assume to be invalid. The loop iterates through all sections and erases certain fields using an array of offsets and one hardcoded offset. However only the hardcoded offset 0x20 seems to be correct, it resolves to Linenumbers Number. The other offsets point to data in between fields as previously mentioned.

Some comments on the code

Importing native functions like ZeroMemory and VirtualProtect is a pretty big hint for reverse engineers, that there will likely be some kind of data manipulation or memory manipulation going on. Native imports are also quite easy to spot even when obfuscated, due to the DllImport attribute containing the dll’s name aswell as the EntryPoint which is the name of the function that is imported. This however is the case for basically every AntiDump that relies on PE Header manipulation, since by default the memory region of the PE Header is marked read-only. To change this and enable write permissions it is hard to circumvent calling either VirtualProtect or VirtualProtectEx*.

Coming back to this specific implementation, the way VirtualProtect is used here is highly inefficient, as it is called for every offset in the array while all offsets are in a certain range within the PE Header. Since the offsets of the fields that are being erased are known one could simply change the memory protection for the entire range until the biggest offset. Changing the protection once for this range and then restoring it after completing all overwrites would be a lot more efficent. Additionaly I would utilize 0x04 (READ_WRITE) for memory protection as thats sufficent for overwriting/erasing values. Another point I would critique: A lot of the fields being erased are zero by default, so overwriting them seems pointless. The biggest issue in my opinion: All offsets are hardcoded for PE32 which means the code only works on 32bit applications.

*You can also use NtProtectVirtualMemory but its undocumented and does not offer any particular benefit over normal VirtualProtect.

Modifying the PE Header

Instead of simply erasing data from the PE Header why not change a few values to break common dumpers. To understand what we need to modify we will take a quick look into how dumpers like ExtremeDumper parse the image in memory.

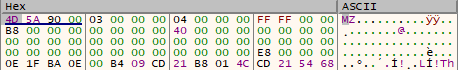

In order to dump the image in memory ExtremeDumper will parse the PE Header. The PE Header contains important information about the structure of the file. This includes the virtual addresses of the sections, the machine type and import address table. The structure of the header is mostly the same everytime it starts with the DOS Header which is 60 bytes in size. The DOS Header does not contain much information apart from the offset to the File Header and the PE signature MZ (also called PE Magic). You can erase the entire DOS Header from memory on runtime and your app will run just fine, since the PE Loader and CLR only require the DOS Header for initialization.

The File Header that follows the DOS Header however is a bit more important, it contains information like the number of sections and the size of the Optional Header. These two values are actually the most important ones for further processing.

ExtremeDumper, or rather dnlib which is used to parse the PE Header, requires the value of SizeOfOptionalHeader to correctly parse the Optional Header and calculate the correct image size. After some testing it turned out that changing the value of SizeOfOptionalHeader only works for x64 compiled binaries and only with short.MaxValue. I could not find the exact reason for this behavior but it seems like x64 binaries are loaded differently by the CLR compared to x86 binaries.

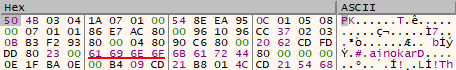

While checking the DOS Header parser of dnlib I noticed that simply changing the PE Signature, or erasing it, is enough to abort parsing by dnlib. Which means we could just replace the DOS Headers PE Signature with something else for example the signature for a ZIP file. It will look like a valid header in memory instead of being a block of zero bytes followed by the File Header.

The example uses a 32bit C# console application.

This is a dump of the original PE Header notice the PE Signature MZ

or as dnlib reads it 0x5A4D

This is a dump of my modified PE Header notice the Signature changed to PK which is actually for ZIP files. Dnlib would in this case read 0x4B50 as the Signature and abort further parsing.

While changing values in the PE header is quite successful for many dumpers, some dumpers are actually able to deal with it just fine. One problem with PE Header manipulation is that we only modify the image in memory but not the image on disk. Many dumpers have features that compare the two versions of the image and can thereby fix some overwritten values. In the next section I will go into the different approaches one could take to counter runtime PE Header manipulation.

An example implementation of the above described can be found here

Code references:

ExtremeDumper NormalDumper.cs | dnlib PEInfo.cs | dnlib ImageDosHeader.cs

Countering AntiDump protections

Using the disk image

As you might have noticed most of the above mentioned protection schemes rely on PE Header manipulation on runtime, meaning the PE Header on disk is almost always completely fine. A simple way to mitigate erased PE Header info is just comparing the dump to the disk image and fixing unusual or missing data. You can even do that on runtime parsing both disk image and memory image checking them against each other. If we find anomalies, such as an invalid value for SizeOfOptionalHeader, we can compare those invalid values with the original data from the disk image and then replace them if necessary. Another solution is checking redundant fields of the PE Header for example we could check if the machine type adds up with the size of the Optional Header. The Optional Headers size will by default always be the same for x64 and x86. So checking the machine type can give us a hint for the correct size even if it was changed. Many more complex AntiDumps techniques will also erase .NET metadata. In that case using the disk image for comparison is again a great way to fix the issue.

Patching the binary

What you can also easily do most of the time, is removing the AntiDump method from the binary or if that is not possible, hook it using Harmony for example. How exactly the hook looks like is not that important as there are many different ways to patch the AntiDump. When looking for AntiDump methods in virtualized code or heavily obfuscated code you can almost always rely on the required usage of VirtualProtect or any other memory protection function. This means that by using either a Debugger or a API monitoring tool we can find the code region that calls VirtualProtect and patch it or hook it. However this requires knowledge of assembly code.

Bonus: “Hiding” P/Invoke methods

One big issue with many AntiDumps is that they need to use P/Invoke to import native functions, which is easy to spot for reverse enginners. What can you do to obscure or hide the imports of native functions? Let us have a look at a couple of methods to hide the imported functions.

Dynamic invoking

For this we will dynamically resolve a functions address using GetProcAddress. The disadvantage of this method is obviously that we still have to use a P/Invoke method, however we can obfuscate the name of the actual function we want to call.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

[DllImport("kernel32", CharSet = CharSet.Ansi, ExactSpelling = true, SetLastError = true)]

private static extern IntPtr GetProcAddress(IntPtr hModule, string procName);

[UnmanagedFunctionPointer(CallingConvention.StdCall)]

private delegate uint PVM(IntPtr ProcessHandle, ref IntPtr BaseAddress, ref uint numberOfBytes, uint newProtect, out uint oldProtect);

public static IntPtr GetLoadedModuleAddress(string dllName) {

var procModules = Process.GetCurrentProcess().Modules;

foreach(ProcessModule mod in procModules) {

if (mod.ModuleName != dllName)

continue;

return mod.BaseAddress;

}

return IntPtr.Zero;

}

private static IntPtr GetFunctionPointer(string dllName, string functionName) {

var hModule = GetLoadedModuleAddress(dllName);

return GetProcAddress(hModule, functionName);

}

First we import GetProcAddress from kernel32.dll using DllImport. Next we define a delegate with the UnmanagedFunctionPointer attribute since we will cast a native function pointer to this delegate later. The delegate PVM is for NtProtectVirtualMemory from ntdll.dll which is the underlying function of VirtualProtect. The GetLoadedModuleAddress function will get the base address of the specified ProcessModule from the current process. The most important function GetFunctionPointer gets the native function pointer of the specified function from the specified dll. Im using this method instead of GetModuleHandle to avoid further native imports.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

public static void Protect() {

string dllName = Encoding.UTF8.GetString(Convert.FromBase64String("bnRkbGwuZGxs")); // ntdll.dll

string functionName = Encoding.UTF8.GetString(Convert.FromBase64String("TnRQcm90ZWN0VmlydHVhbE1lbW9yeQ==")); // NtProtectVirtualMemory

var fPointer = GetFunctionPointer(dllName, functionName);

PVM pvm = Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer<PVM>(fPointer);

var p = Process.GetCurrentProcess();

var @base = p.MainModule.BaseAddress;

uint size = 0x3C;

pvm(p.Handle, ref @base, ref size, 0x04, out uint oldProtect);

Marshal.Copy(new byte[size], 0, @base, (int) size);

pvm(p.Handle, ref @base, ref size, oldProtect, out _);

}

Let’s look into the actual protection code. First we specifiy the dllName and functionName parameters for GetFunctionPointer. I use simple Base64 Encoding in this example but you can use any kind of string encryption or encoding to obfuscate the names. Next we call GetFunctionPointer with the supplied names to obtain the address of our desired function. In this situation, I resolve the address to NtProtectVirtualMemory in ntdll.dll. We assign the delegate by casting the obtained address to a delegate using Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer<T>.

After assigning the delegate we get the current process and obtain the base address of its main module. Using the base address and a handle to our current process we call the pvm delegate to change the memory protection of the first 60 bytes (size of the DOS Header) of our module to 0x04 (READWRITE). We then copy an array of zero bytes to the location of the DOS Header thereby overwriting it entirely with zero bytes. Last we restore the memory protection of the DOS Header back to the old protection.

This might not be the best way of hiding native imports but it is better than simply exposing them without any kind of obfuscation.

The used example code can be found here

Syscalls

This will implement direct syscalls completely avoiding exposing the funtion name or its dll name. It will also bypass basic usermode hooks on the functions we are syscalling. Disadvantages of this method are that it relies on native shellcode and we can only call functions that exist as a syscall.

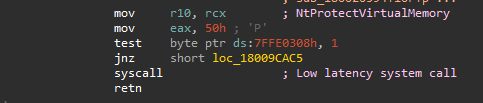

In order to do a syscall we need to look at the function we are trying to syscall in my case NtProtectVirtualMemory also known as ZwProtectVirtualMemory. Lets check the function in IDA to see how the syscall is implemented.

64bit version of ntdll.dll

The index of the syscall in this case 0x50 (50h) is pushed into eax. The syscall instruction will use the index in eax to resolve the function its supposed to call.

Since C# does not support inline assembly, we will need to create shellcode to syscall from our managed app.

1

2

3

4

mov r10, rcx

mov eax, 0x50

syscall

ret

Basically we just copy the function dissassembly from IDA but remove the test and jnz instruction. This pattern is pretty much the same for every syscall except the index thats pushed into eax. (This shellcode only works for 64bit apps)

Lets implement this in C#. We will need to import kernel32.dll VirtualProtect. And just as in the dynamic invoke example we need a delegate for NtProtectVirtualMemory.

(You could combine this with the native invoke to hide the VirtualProtect import)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

private static PVM pvm;

private static byte[] Shellcode = {

0x49, 0x89, 0xCA, // mov r10,rcx

0xB8, 0x50, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // mov eax, 0x50

0x0F, 0x05, // syscall

0xC3 // ret

};

static Suscall() {

fixed(byte* ptr = &Shellcode[0]) {

if (!VirtualProtect(ptr, (uint) 10, 0x40, out _)) throw new Win32Exception();

pvm = Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer<PVM>((IntPtr) ptr);

}

}

The above assembled shellcode is stored as raw bytes. The Suscall function is a static constructor to initialize the shellcode and cache the delegate. This process is pretty similar to the dynamic invoke example however instead of resolving the function pointer we allocate the shellcode in a fixed buffer and then cast it to our previously defined PVM delegate. The delegate will directly call the syscall just like NtProtectVirtualMemory does. Using this we don’t need to invoke the NT function anymore, thereby also preventing a debugger from just setting a breakpoint on the function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

public static void Protect() {

var p = Process.GetCurrentProcess();

var @base = p.MainModule.BaseAddress;

uint size = 0x3C;

pvm(p.Handle, ref @base, ref size, 0x04, out uint oldProtect);

Marshal.Copy(new byte[size], 0, (IntPtr)@base, (int) size);

pvm(p.Handle, ref @base, ref size, oldProtect, out _);

}

The protection implementation remains mostly the same as before, but we call the cached syscall delegate to directly execute the underlying functionality of NtProtectVirtualMemory. This implementations looks a lot cleaner since the only thing that statically exposes the called function is the syscall index. To further obfuscate this you could encrypt the array containing the shellcode, so its harder to analyze statically.

One issue with allocating shellcode and syscalling is that it might be picked up as malware by an antivirus due to the more and more common usage of syscalls in malware. To avoid shellcode usage you could implement this as a native method which would also eliminate the need to use VirtualProtect.

The code for this example can be found here

Conlusion

I think this write up goes to show that simple PE Header manipulation might not be the best way to prevent people from dumping your app. However more complex approaches that involve .NET metadata manipulation can be quite effective against low skill attackers as they will require a lot more effort and knowledge to fix.

I hope the bonus segment on hiding P/Invoke methods gave some good ideas on how to obscure/obfuscate native imports. As I think obscuring native imports could be an improvement for some people. If you have any questions regarding the contents of the write up feel free to contact me on discord: drakonia#1110.